Photo by Christina Morillo on Pexels

Photo by Christina Morillo on Pexels Thousandth Line of Code

Write right things

“Task has been set, it needs to be carried out. At the end of the day, you are an expert” as the once-popular sketch told us. So you jump right into the fray, to the stuff that matters. Line after line, your code takes shape. SQL statements populate the schema that you’ve just created, and the threads are ready to be spawned; your code --- a masterpiece contained within a thousand lines.

Ask yourself a question - does anything you have written in those thousand lines actually bring value? Let me rephrase what I’ve just said - what is the goal of the feature you set out to create?? Was it ”(…) clever queries with SQL (…)” or maybe ”(…) efficient utilization of CPU (…)”? Or maybe something like, “as a salesman, I want to refresh the view on demand, to be able to show current offer to the customer.”

A simple user story, yet powerful. There is no mention of threads, not a word about databases, not even a vague hint about performance. And the reason why is actually quite obvious - because it does not matter. Not at this point, perhaps never.

Disclaimer

I am writing from a position of developer involved with business-heavy applications, so don’t expect this to apply to embedded code! What I’ve written here will not necessarily apply to libraries or frameworks as well. Moreover, everything presented here is a matter of trade-off and should be treated as such. As a consequence, you will find this interesting specifically if you work with E-type program. I firmly believe that software should address real-world problems, and so should we.

Our priorities are wrong

The heart of software is its ability to solve domain-related problems for its user.

- Eric Evans, Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software

We as developers value code that’s efficient, clever - this is after all what we are supposed to do, this is what 10x rock⭐star developers honed their skills for!

Except it is not.

Our job is not to write code. Our job first and foremost is to use our knowledge as programmers to provide a solution to a business problem; not to brag how unreadable/perfect our one-liner is. Your job is to solve problems.

What we ought to do is to place the “domain problem” at the pedestal, as the problem to be solved. Of course solution in itself cannot exist in a vacuum, yes - it requires dependencies: persistence, some kind of user interface and so on *. But still, the very core of our problem is business oriented, we should not prioritize dependencies. In fact, a solution should work independently from dependencies *, should be testable and verifiable regardless of how those dependencies are coded. And if that means not using some clever optimization hack or sacrificing some performance along the way… Then said optimization, so lauded by hackathon winners, never mattered after all.

Not everything is about code

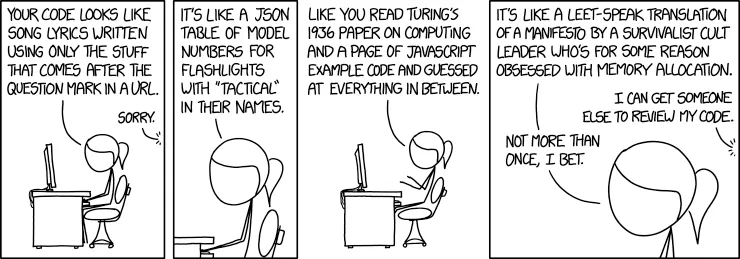

Comic by XKCD

Coding a system larger than what you can maintain alone is more than just about writing code. It should be written in a way that is and will be understood by the team, arguably to the point that non-technical person can read it just as well as you do. Because the problem is, as noted time and time again, that you read code more often than you write it. As a matter of fact, “ratio of time spent reading versus writing is well over 10 to 1.” *. So hand in hand with the previous point, if you have to sacrifice some performance to align code with domain knowledge, to make it readable, malleable, go for it! Because code can always be optimized when needed; and the input that you can get from aligning the code to domain expert’s knowledge is invaluable. And the time not wasted by your peers on digging through piles of cleverness is a time and money saved.

In the next couple paragraphs, I’ll illustrate certain viewpoints that I wish you to go through.

Big picture, small picture

We tend to work on a smaller scale - us, developers. Connect with this, send event here, consume that. We sadly avoid immersing ourselves with the domain and the problems that are actually relevant to what we produce. We do not try to understand product’s value; we do not walk a mile in Product Owner’s shoes. We write solutions to technical problems ignoring their real value. But the programming is a balancing act; and when we set our mind to do the work, it’s easy to forget that we often focus on the detail where detail is not as important.

Consider this as a matter of trust. Typically, we work in a structured environment. Product owner * will tell us what he or she expects. We need to trust that what we are being told that has to be done will make the most of our time. And sometimes, we find out for example that current architecture is unfit to the solution. Don’t be afraid to settle differences by talking. You don’t have to understand the big picture, but you have to trust that someone does - and if you present your concerns, then things that you see as problematic - in example, architecture - Product Owner can prioritize technical work when needed, because it is his job to decide about priority of a task, but it is up to you to help him understand how valuable (Or costly!) such change is. If you do not, then you risk that PO will make the decisions without your input.

Solving the problem that never was

From the perspective of a developer, it is certainly tempting to go for low hanging fruits. We see that we can optimize if we just violate this separation a bit. Tick, one day added to our work. We can make it efficient by doing something else. Tick, another day. And from the estimated half of a sprint, you suddenly are working on a problem for the second month. And the sad truth is, your work is most likely unnecessary. You can see the potential for a problem, but until the problem has materialized and its impact is measurable, then it is a non-issue.

I’ll hammer my point again. If the work you do have no real-world impact, then it’s a waste. So stop worrying about technical issues that much.

It’s a pendulum

There is another side of things still. While I prefer to see business side of things as more preferable to focus on, and technical issues as the less important things to focus on, there is a stark difference between hyper-focusing on technical issues and not taking care about your work. I’d argue, that you have to spend more time thinking about design and architecture instead of code.

Jon Eaves* said: “Microservice can be rewrote in 2 weeks or less”, and so I urge you to apply similar mindset to your code in any framework or language: design your solution so it can be rewritten swiftly and without a hassle. Focus on the seams, not on the internals, and you’ll do just fine.

How problem solving becomes a problem in itself: An example

Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand.

- Martin Fowler, Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code

There was an application that was created to facilitate batch calculation per user, with different calculation Definitions that could be assigned for each user. It was designed as performant application - before any code has been written - database model was created, algorithm steps were defined, in essence, typical waterfall project. All designed around the idea that definition was central, and so calculations were performed by loading definition, then users assigned to said definition.

This approach was valid till the first actual usage. Amongst plethora of other problems, one problem that bit us the most was that there was no possibility to recalculate a single user after error, as system was designed to allow for recalculation of whole definition, not particular users.

Solution was orthogonal to how business operated. There was never complaint about definition, but always about a customer. Moreover, the very first use-case broke the main promise. Solution was neither performant, as definitions could be customized per user, massively increasing the volume of definitions, nor easy to code within. And the worst part? There were around ~200k users, and around 5,000 Definitions, with multiple Definitions assigned to a single user - we couldn’t cache customers and caching definitions provided no real benefit. Worse still, developers were so afraid to change code according to new knowledge, that we have tried to cram everything into existing solution!

Had the system be designed around the business itself, we could scale per user, up to a theoretical limit of an instance per user. We were stuck because single definition calculation required us to place locks on a user.

It had cost us few hundred man days to correct this, all the while bringing basic business cases as first-party to the system. Had it been done from the start, we could have scale-able system with API that would allow for business operations to be seamlessly implemented. Instead of that, we had buggy solution that had to be worked around to do anything.

Of course, it was an application build under my care. I find no consolation in the fact that I couldn’t change a thing from the design that was handed down on me at first. Problem was very real and very painful.

Because someone believed in optimization before actual demand.

Because someone wanted to be smart.

Details are not goals - Illustration of problem

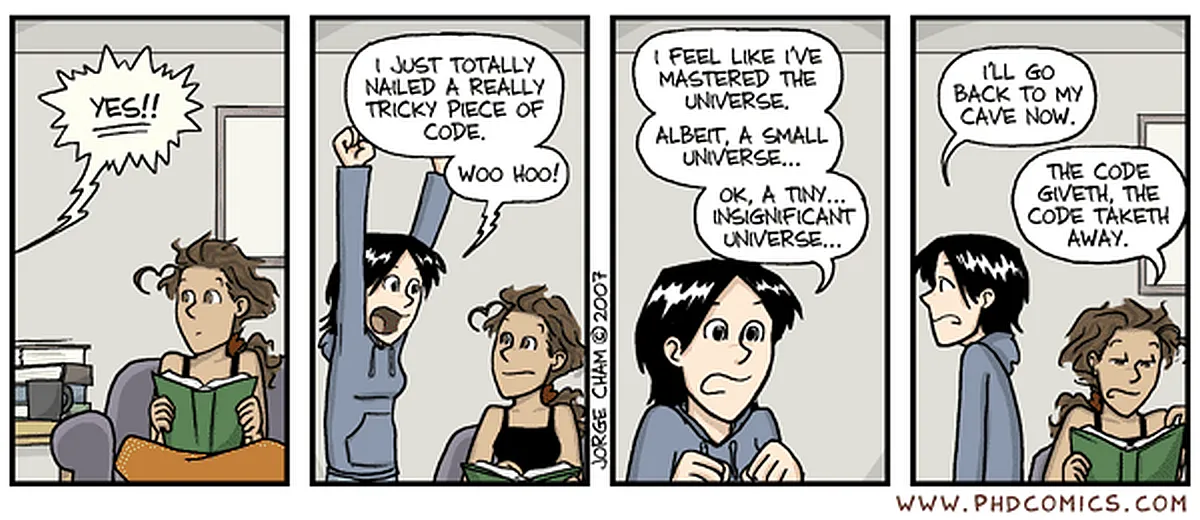

Comic by Jorge Cham

Imagine yourself sitting before your keyboard, tackling yet another task. What is the very first thing that you write? Start with the contract. Write the tests for the contract. Implement the contract. This is the real value of your work. Make sure that the code you write reflects what you are set to do. Take inspiration from how business is doing the stuff you are writing down and reflect their experience. How to actually store the data? How to handle API calls? All of this is an implementation detail to a generic problem, so do them as cheaply as you think is okay. Clever, efficient code can be done later and absolutely should be done later, because you do not know how much value your optimizations will bring. When it comes to limited amount of time, attention should always be on the business side delivered with minimum amount of waste. Dependencies are least important in the equation. Does it really matter if it’s called via REST or SOAP? Or that it’s stored as an event stream, in relational or in document database? Or maybe in flat file, in the first version.

This problem is neatly solved via OOP patterns. Create Repository interface for your persistence. Implementation can be done cheaply, and refactored without any risk, because it was kept where it should. As a detail.

Of course, you can always shave 20% from the application load by compromising separation by design, but should you do it?

I argue, that until proven otherwise absolutely not. Technical excellence is not a goal in itself. 20% may sound scary, but in the long term, what is 20% if it changes overall load from 10% to 12%, compared to the scab of a code that will have to grow around your improvement.

Until you are absolutely sure, don’t do it.

You can always think about it this way - new instance of your application will cost business, let’s say $200 per month. Such instance will double the performance. You can write your 20% optimization in a week. On average, mid level developer in US has salary of 34$ per hour. With all the costs factored in, it translates to $50 per hour per developer (Cost of office, infrastructure et cetera). You need 40 hours - $2,000 - to add 20%; all the while you are not doing other tasks. 20% increase for $2,000 with hopes that it will be actually needed, or $200 per month for 200% increase. Let that sink in.

Do the right thing

Following up on the previous example, we have recoded system to align it with business needs. Mean time of a task execution went from an around week or two of work (with manual corrections in the database) to half a day via API. While it did not address all the issues, doing the right thing from the start could’ve saved us months of work.

But even having that in mind, “just enough” is not enough sometimes. Persistence was relegated to a supporting role, but real data showed us that we were choking the database with performance far below expected. It was clear that in the pursuit of clean separation we have overdone it and ignored the technical details.

So we went and did literally three optimizations to the database and queries - Indices, Ahead Of Time fetching and filtering in query instead of memory. It took us four days. Performance was slightly below original approach (mostly because persistence was not suited to the needs, but that’s a whole different story.) It reduced our maintenance cost by a factor of tens or even hundreds; while giving us an opportunity to easily scale horizontally.

Do the right thing, by doing the thing right precisely when you need it and not a moment sooner.

Bruised egos

(…) if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.

- Abraham Maslow, The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaisance

There will always be push-back. Whole generations of developers were taught that software is the goal onto itself. Will you have the courage to say out loud: I will gladly sacrifice readability if you can squeeze one less if statement? Will you have the courage to admit that you will spread business logic between application and database just because you are certified database Guru?

Will you proudly proclaim - As a 10x developer I’ve just made application 10x times as hard to maintain just to flex my skills? I hope not.

If you are skilled vertically, that is in one single area of expertise, use your skill! But don’t loose focus. Your skill can be a perfect hammer, but not every problem is a nail. Software in its core is soft, you can do almost anything with any language, framework or tool. That does not mean that you should. Trust your product owner. Trust your teammates. You can have a great hammer, and you can be an expert in ‘hammering’, but this bubbly geek girl at the other side of the room might just have a perfect saw at her tool belt.

Just don’t try to cut with the hammer. Please.

Closing words

You Can’t Write Perfect Software. Did that hurt? It shouldn’t. Accept it as an axiom of life. Embrace it. Celebrate it. Because perfect software doesn’t exist.

- Andrew Hunt, The Pragmatic Programmer: From Journeyman to Master

We developers have limited opportunity to do things right. Constraints are everywhere, either we are understaffed, underfunded or we have the deadline looming just around the corner. Sometimes, we lack just about everything. So what can you do in a situation like this?

I’m calling out to you.

First thousand lines. Use them for what really matters, write the right thing.

Further reading

- Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software by Eric Evans

- Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship by Robert C. Martin

- Clean Architecture: A Craftsman’s Guide to Software Structure and Design, First Edition by Robert C. Martin

- The Pragmatic Programmer: From Journeyman to Master by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas

- Scrum Guide by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland